These days, there is precious little boxing that takes place over the holidays, save for the customary late-year shows in Russia and Japan. For promoters, it’s a financially perilous decision to stage a show at this time of year, with potential ticket buyers and broadcast viewers’ time and money already allocated in many places. For fighters, already laborers in a sport that requires a degree of separation from loved ones, having to do so over the holidays is something they’d prefer to avoid. Not to mention, holiday indulgence and making weight don’t exactly go together like mashed potatoes and gravy.

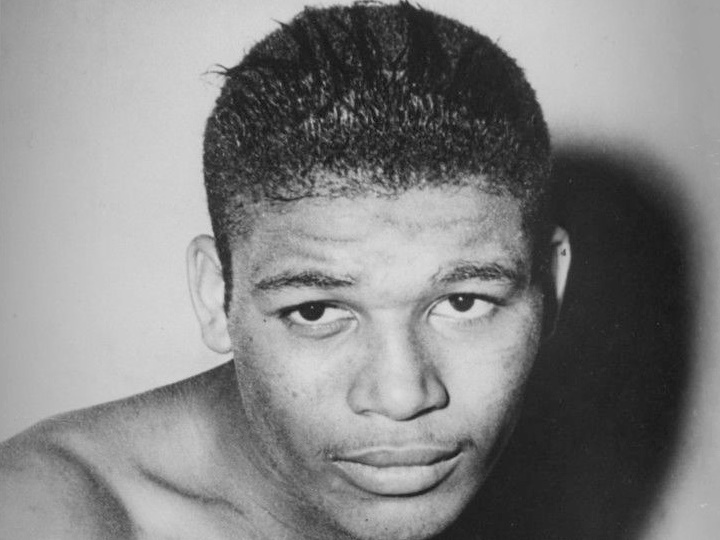

But 71 years ago, the world’s best fighter at the time, and the one who would go on to be accepted as the greatest to ever live, was in action on Christmas Day. On December 25, 1950, Sugar Ray Robinson took on Hans Stretz in Frankfurt, Germany.

Without any context Robinson’s fifth round knockout win over Stretz reads like a nondescript stay busy outing on BoxRec. However, the story of how Robinson got there, what happened while he was there and what subsequently occurred in the wake of it makes his win over Stretz and the preceding European tour a fascinating little slice of boxing history.

In November of 1950, Robinson agreed to take part in a series of bouts across Europe for promoter Charlie Michaelis. Robinson was a notoriously fierce negotiator and distrustful of promoters, particularly as his star began to brighten, but he trusted Michaelis, and even fought one of the bouts on the trip without a formal agreement, finding it unnecessary because he knew Michaelis would be straight with him. Michaelis originally purchased four round trip tickets for Robinson, but he decided that wouldn’t be enough. Robinson wanted to travel with the same crew he would for a fight in the United States, including his wife Edna Mae, his barber and valet, his spiritual advisor, and more. Together they had 53 pieces of luggage, all identified as theirs with red strings tied to the handles.

Robinson et al travelled on the SS Liberté, a repurposed German ship transformed into a luxurious cruise ship with opulent French service. Robinson would later remark in his autobiography how unusual it was for nine Black Americans to be on a cruise ship of this nature, but the Liberté and the Parisians’ comparatively more progressive views about race would become a selling feature for many prominent Black celebrities of the time. Notables such as Sarah Vaughan, W.E.B. Du Bois and Beauford Delaney all sailed to Paris on the Liberté in the 1950s.

Robinson is considered by many to be the one who popularized the celebrity entourage. The origins of that term, for Robinson at least, are rooted in this voyage. It’s on this ship that Robinson heard a crew member refer to “Robinson and his entourage.” Robinson liked the sound of the term, its mouth feel as it rolled off his tongue, and found it to be a more respectful descriptor than “associates.” The name would stick.

In Paris, Robinson found a level of reverence and celebrity he hadn’t yet experienced in America. Admirers treated him as “un artiste,” and the city’s appreciations for the arts and fashion were alluring to Robinson. As he did seemingly regardless of where he was, Robinson found his way to where women were, and in a nude dancing club, Robinson met the man who would become the tenth member of his newly anointed entourage, the 4-foot-4 Jimmy Kapoura. Kapoura, who spoke several languages, including French fluently, offered to become Robinson’s translator on the spot. No further negotiation was needed. By the next time Robinson had a European tour the following year, he’d added a 13th member, a second person of short stature, Arabian Knight, to be his “mascot” and hype man.

Sugar Ray’s European loop consisted of five fights in 29 days, an unfathomable pacing of fights in the modern landscape, even for prospects wiping out opponents in four rounders, let alone the sport’s elite. All of the fights were contested at middleweight, as Robinson prepared for his major jump up in weight to face Jake LaMotta for the 160-pound title. Robinson had made his last defense of the welterweight crown against Charley Fusari in August and had somewhat quietly decided to leave the division that fall, although The RING still considered him its 147-pound champion.

His opposition compared to Sugar Ray Robinson was obviously lackluster, but in the grand scheme of things, his opponents were all solid fighters, some of the best Europe had to offer in the middleweight division at the time. He knocked out Jean Stock in France, stopped Luc Van Dam in Belgium, decisioned Jean Walczak in Switzerland, and flattened Robert Villemain back in France again. Some of the bouts were arranged on the fly while Robinson was already in Europe, such as the Villemain bout. After Robinson’s win over Stock, Villemain was in attendance and joked to reporters that Sugar Ray was his next big opponent. Robinson thought he was serious, and within five minutes had agreed to face him in late December. This was how utterly unconcerned Robinson was with the possibility of anyone beating him while in the midst of a 91-fight winning streak.

“It’s hard to imagine any other champion doing what did when he agreed to fight an unknown fighter in a strange city two days after a hard fight with Villemain,” said James McGovern in a letter from Frankfurt which was printed in Red Smith’s syndicated column on January 11, 1951. “The Germans love a show of strength, and Sugar Ray gave them that in spades.”

Stretz might not have been as unconcerned as Robinson, but he was somewhere between naïve and ignorant to what was to come. He trained in an unheated air force base, perhaps to prepare himself for the conditions in the Haus der Technik, the venue the bout would be staged in, which was also without heating. As studious as he might have been in readying for the climate however, he wasn’t as diligent or anxious about what the greatest fighter who ever lived had in store for him. Stretz admitted to McGovern that he’d never seen Robinson fight before. Reportedly while hugging himself to stay warm, he offered a classic pre-fight soundbite.

“Anything can happen in boxing. The worst sometimes beat the best, and I’m not the worst,” he said.

The night before the Stretz bout, German children braved the snowstorm to sing Christmas carols outside of Robinson’s hotel window as he gazed out longingly, now finally missing the comforts of home in New York City. As his manager George Gainford always told him to do, Robinson wanted to finish the fight as quickly as possible and get back on the Liberté back home two days later.

Decked out in matching purple jackets with “Sugar Ray” sewn onto the back, Robinson strolled to the ring with his entourage inside the frigid venue. Somewhere between 7000 and 10,000 people attended the fight, but not even raucous shouting and bodily warmth could heat the venue up much, particularly for the shirtless fighters. Ringside reports suggested that Robinson didn’t had a bead of sweat on him—which likely had as much to do with the temperature as the ease of his assignment.

Robinson floored Stretz in the opening 30 seconds of the bout, and an additional seven times, before Stretz finally remained on the canvas in the ninth round. Reporters marveled at Stretz’s ability to seemingly be revived by the sound of “nine,” a la Tyson Fury against Deontay Wilder, but there would be no heroic ending for Stretz.

There was somewhat of a hero’s celebration for Robinson however, not just from the adoring German public, but from the many American GIs who were in attendance. Soldiers tried to rush the ring to carry Robinson back to his locker room, but were stopped by local police.

In all, Robinson made roughly $50,000 for his European tour, but admitted that he spent virtually all of it by the time he arrived back in the United States.

While Robinson was packing his 53 bags to head back home, RING editor Nat Fleischer announced the publication’s annual awards. At this point in time, the term “pound-for-pound” had been used in relation to Bob Fitzsimmons, Henry Armstrong and others, but there was no “formal” (such that it can be) designation or ranking by the publication as of yet. The day he defeated Stretz, Robinson received the honor of “best all-around fighter” from Fleischer. Ezzard Charles was given Fighter of the Year, but Fleischer wanted something to honor the fighter who might not have had the best year overall in 1950, but was clearly the sport’s best fighter nonetheless. It is perhaps the precursor to the pound-for-pound title, something that has become inextricably linked to Robinson. Two weeks later, the Boxing Writers Association of American honored Robinson for “doing the most for the sport in a given year,” a gesture to acknowledge Robinson’s donation of all by $1 of his purse against Fusari (roughly $50,000) to the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.

As he was waiting to receive his award at the dinner gala, the MC began to read telegrams from those unable to attend the event. The most notable was one from Jake LaMotta, which read: “See you in Chicago on February 14. Make sure you’re there. -Jake”

Robinson would of course go on to defeat LaMotta in what was subbed the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, one of the most memorable bouts of all-time, to win the world middleweight crown. The month-long tour of Europe that preceded was a important bridge period, one that marked the end of Robinson at welterweight—perhaps the best version of any fighter ever—and a new beginning at middleweight. It formalized the name of Robinson’s crew, perhaps started the practice of referring to him as the pound-for-pound best, and gave him a worldly experience that colored his approach to his life from then on. The mythology of Sugar Ray Robinson was forged, in part, on this voyage.

As they stepped off the Liberté, Robinson’s valet June Clark, whom he’d employed and taken care of after a bout with tuberculosis, assured Sugar Ray that they would be back in Europe soon.

“I’m keeping the red strings on all the bags,” he said.

Corey Erdman is a boxing writer and commentator based in Toronto, ON, Canada. Follow him on Twitter @corey_erdman